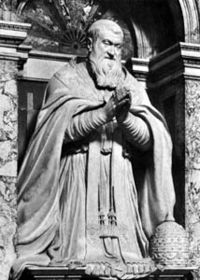

Pope Sixtus V

| Sixtus V | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Papacy began | 24 April 1585 |

| Papacy ended | 27 August 1590 |

| Predecessor | Gregory XIII |

| Successor | Urban VII |

| Personal details | |

| Birth name | Felice Peretti di Montalto |

| Born | 13 December 1520 Grottammare, Papal States |

| Died | 27 August 1590 (aged 69) Rome, Papal States |

| Other Popes named Sixtus | |

Pope Sixtus V (13 December 1520 – 27 August 1590), born Felice Peretti di Montalto, was Pope from 1585 to 1590.[1]

Contents |

Biography

Early life

The chronicler Andrija Zmajević believed that Felice's family originated from modern-day Croatia/Montenegro[2]. Felice's father, Piergentile di Giacomo, had been born in Bjelske Kruševice, a village near Bijela in the Bay of Kotor, into the Croatian[3] Šišić family; moving to Italy to escape the Turkish invasion, and settling in Ancona as a gardener and subsequently a swineherd.

Felice Peretti was born in December 1520 at Grottammare, in the Papal States, to Piergentile, nicknamed "Peretto", and Marianna da Frontillo. Felice later adopted "Peretti" as his family name in 1551, but was more generally known as "di Montalto"[4]. He was reared in poverty; born in a shanty allegedly so ill-thatched that the sun shone through the roof, he later jested that he was "nato di casa illustre" — born of an illustrious (i.e. "illuminated") house.

Not much else is recorded about Peretti's family, but when he eventually became Pope Sixtus V, the church of Saint Jerome in Rome was rebuilt to be used specifically for the people who spoke the Illyrian language. He also established a college of eleven Slavonic clerics in his papal bull Sapientiam Sanctorum of 1 August 1589. This was later transformed into the Pontifical Croatian College of St. Jerome.

At an early age he entered a Franciscan friary at Montalto and was known as Felice di Montalto. He soon gave evidence of rare ability as a preacher and a dialectician. A legend has it that while a friar he was approached by the ageing Nostradamus who knelt, kissed the friar's robe and then exclaimed he was kissing the robe of the future pope.

About 1552 he was noticed by Cardinal Rodolfo Pio da Carpi, protector of the Franciscan order, Cardinal Ghislieri (later Pope Pius V) and Cardinal Caraffa (later Pope Paul IV), and from that time his advancement was assured. He was sent to Venice as inquisitor general, but was so severe and conducted matters in such a highhanded manner that he became embroiled in quarrels. The government asked for his recall in 1560.

| Papal styles of Pope Sixtus V |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Reference style | His Holiness |

| Spoken style | Your Holiness |

| Religious style | Holy Father |

| Posthumous style | None |

After a brief term as procurator of his order, he was attached to the Spanish legation headed by Ugo Cardinal Boncampagni (later Pope Gregory XIII) in 1565, which was sent to investigate a charge of heresy levelled against Archbishop Bartolome Carranza of Toledo. The violent dislike he conceived for Boncampagni exerted a marked influence upon his subsequent actions. He hurried back to Rome upon the accession of Pius V, who made him apostolic vicar of his order, and, later (1570), cardinal.

During the pontificate of his political enemy Gregory XIII (1572–85) the Cardinal Montalto, as he was generally called, lived in enforced retirement, occupied with the care of his property, the Villa Montalto, erected by Domenico Fontana close to his beloved church on the Esquiline Hill, overlooking the Baths of Diocletian. The first phase (1576–80) was enlarged after Peretti became pope and could clear buildings to open four new streets in 1585–6. The villa contained two residences, the Palazzo Sistino or "di Termini" ("of the Baths") and the casino, called the Palazzetto Montalto e Felice. Displaced Romans were furious. The decision to build the central pontifical railroad station (begun in 1869) in the area of the Villa marked the beginning of its destruction.

Cardinal Montalto's other concern was with his studies, one of the fruits of which was an edition of the works of Ambrose. As pope he personally supervised the printing of an improved edition of Jerome's Vulgate -- said to be "as splendid a translation of the Bible into Latin as the King James version is into English."[5]

Papacy

Election as pope

Though not neglecting to follow the course of affairs, Felice carefully avoided every occasion of offence. This discretion contributed not a little to his election to the papacy on 24 April 1585 taking the title of Sixtus V; but the story of his having feigned decrepitude in the conclave, in order to win votes, is pure invention. One of the things that commended his candidacy to certain cardinals may have been his physical vigour, which seemed to promise a long pontificate.

The terrible condition in which Pope Gregory XIII had left the ecclesiastical states called for prompt and stern measures. Against the prevailing lawlessness Sixtus proceeded with an almost ferocious severity. Thousands of brigands were brought to justice: within a short time the country was again quiet and safe. Next Sixtus set to work to repair the finances. By the sale of offices, the establishment of new "Monti" and by levying new taxes, he accumulated a vast surplus, which he stored up against certain specified emergencies, such as a crusade or the defence of the Holy See. Sixtus prided himself upon his hoard, but the method by which it had been amassed was financially unsound: some of the taxes proved ruinous, and the withdrawal of so much money from circulation could not fail to cause distress.

Immense sums, however, were spent upon public works, in carrying through the comprehensive planning that had come to fruition during his retirement, bringing water to the waterless hills in the Acqua Felice, feeding twenty-seven new fountains; laying out new arteries in Rome, which connected the great basilicas, even setting his engineer-architect Domenico Fontana to replan the Colosseum as a silk-spinning factory housing its workers. The Pope set no limit to his plans; and achieved much in his short pontificate, carried through always at top speed; the completion of the dome of St. Peter's; the loggia of Sixtus in the Basilica di San Giovanni in Laterano; the chapel of the Praesepe in Santa Maria Maggiore; additions or repairs to the Quirinal, Lateran and Vatican palaces; the erection of four obelisks, including that in Saint Peter's Square; the opening of six streets; the restoration of the aqueduct of Septimius Severus ("Acqua Felice"); the integration of the Leonine City in Rome as XIV rione (Borgo); besides numerous roads and bridges, he sweetened the city air by financing the Pontine Marshes. Good progress was made with more than 9,500 acres (38 km2) reclaimed and opened to agriculture and manufacture; the project was abandoned upon his death.

But Sixtus had no appreciation of antiquities, which were employed as raw material to serve his urbanistic and Christianising programs: Trajan's Column and the Column of Marcus Aurelius (at the time misidentified as the Column of Antoninus Pius) were made to serve as pedestals for the statues of SS Peter and Paul; the Minerva of the Capitol was converted into an emblem of Christian Rome; the Septizonium of Septimius Severus was demolished for its building materials.

Church administration

The subsequent administrative system of the Church owed much to Sixtus. He limited the College of Cardinals to seventy; and doubled the number of the congregations, and enlarged their functions, assigning to them the principal role in the transaction of business (1588). He regarded the Jesuits with disfavour and suspicion. He meditated radical changes to their constitution, but death prevented the execution of his purpose. In 1589 was begun a revision of the Vulgate, the so-called Editio Sixtina.

Foreign relations

In his larger political relations, Sixtus entertained fantastic ambitions, such as the annihilation of the Turks, the conquest of Egypt, the transporting of the Holy Sepulchre to Italy, and the accession of his nephew to the throne of France. The situation in which he found himself was embarrassing: he could not countenance the designs of heretical princes, and yet he mistrusted Philip II of Spain and viewed with apprehension any extension of his power.

Sixtus agreed to renew the excommunication of Queen Elizabeth I of England, and to grant a large subsidy to the Armada of Philip II, but, knowing the slowness of Spain, would give nothing till the expedition actually landed in England. This way, he saved a fortune that would otherwise have been lost in the failed campaign. Sixtus had Cardinal Allen draw up the An Admonition to the Nobility and Laity of England, a proclamation to be published in England if the invasion had been successful. The extant document comprised all that could be said against Elizabeth I, and the indictment is therefore fuller and more forcible than any other put forward by the religious exiles, who were generally very reticent in their complaints. Allen also carefully consigned his publication to the fire, and we only know of it through one of Elizabeth's spies, who had stolen a copy.[6]

Sixtus excommunicated Henry of Navarre (future Henry IV of France), and contributed to the Catholic League, but he chafed under his forced alliance with Philip II of Spain, and looked for escape. The victories of Henry and the prospect of his conversion to Catholicism raised Sixtus V's hopes, and in corresponding degree determined Philip II to tighten his grip upon his wavering ally. The Pope's negotiations with Henry's representative evoked a bitter and menacing protest and a categorical demand for the performance of promises. Sixtus took refuge in evasion, and temporised until his death on 27 August 1590.

Legacy

As Sixtus lay on his death bed, he was loathed by his political subjects, but history has recognised him as a significant figure in the Counter Reformation. On the negative side, he could be impulsive, obstinate, severe, and autocratic. On the positive side, he was open to large ideas and threw himself into his undertakings with great energy and determination. This often led to success. His reign saw great enterprises and great achievements. He slept little and worked hard. He had inherited a bankrupt treasury, administered his funds with competence and care, and left five million crowns in the coffers of the Holy See at his death.[7]

The changes wrought by Sixtus on the street plan of Rome were documented in the film, "Rome: Impact of an Idea", featuring Edmund N. Bacon and based on sections of his book Design of Cities.

References

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (Eleventh ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (Eleventh ed.). Cambridge University Press. "Pope Sixtus V" in the 1913 Catholic Encyclopedia.

"Pope Sixtus V" in the 1913 Catholic Encyclopedia.

Notes

- ↑ Name and date information sourced from Library of Congress Authorities data, via corresponding WorldCat Identities linked authority file (LAF) . Retrieved on 20 August 2009.

- ↑ Church Chronicle Andrija Zmajević

- ↑ Pandžić, Basil (1954). A review of Croatian history. University of Indiana. pp. 60-61.

- ↑ The Cardinals of the Holy Roman Church - Biographical Dictionary - Consistory of 17 May 1570

- ↑ Durant, Will, "The Story of Civilation: Vol. VII", Chapter ix, p. 241

- ↑ Catholic encyclopedia, "Spanish Armada".

- ↑ Ibid.#3,p.241

External links

- Montalto delle Marche city of Sisto V

- Piazza di Termini, Rome: timeline, including the Villa

- Visit Montalto delle Marche where Pope Sixtus V trained

- FIU

| Catholic Church titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Gregory XIII |

Pope 1585–90 |

Succeeded by Urban VII |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||